President Obama, speaking last week at an NAACP convention on the eve of his historic tour of Oklahoma’s El Reno Correctional Institution, outlined the major components of his vision for the future of criminal justice reform. When it came to the issue of juvenile offenders, he called for a shift in perspective: “We’ve got to make sure our juvenile justice system remembers that kids are different. Don’t just tag them as future criminals. Reach out to them as future citizens.”

These comments came after a year of intense national debate about issues surrounding what some have described as the “cradle-to-prison pipeline,” including the disproportionate policing of black and Latino minors in urban communities and extensive solitary confinement for juvenile offenders on Riker’s Island. Calls for reform often rely on images of teens the system is said to have failed. But more than 70 years ago, they relied on just the opposite, when one incarcerated youth—confined to one of the country’s most notorious state prisons—became the face of reform.

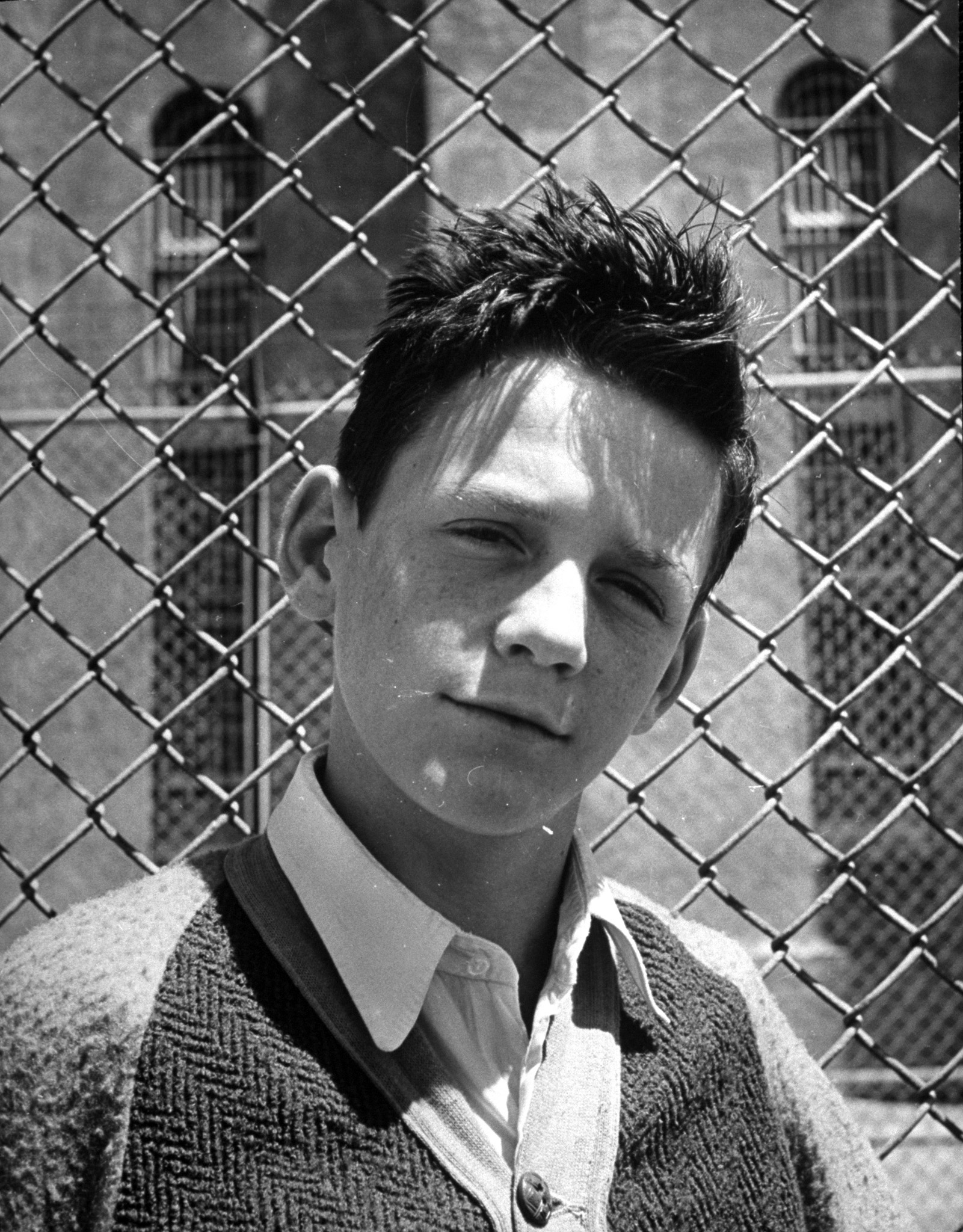

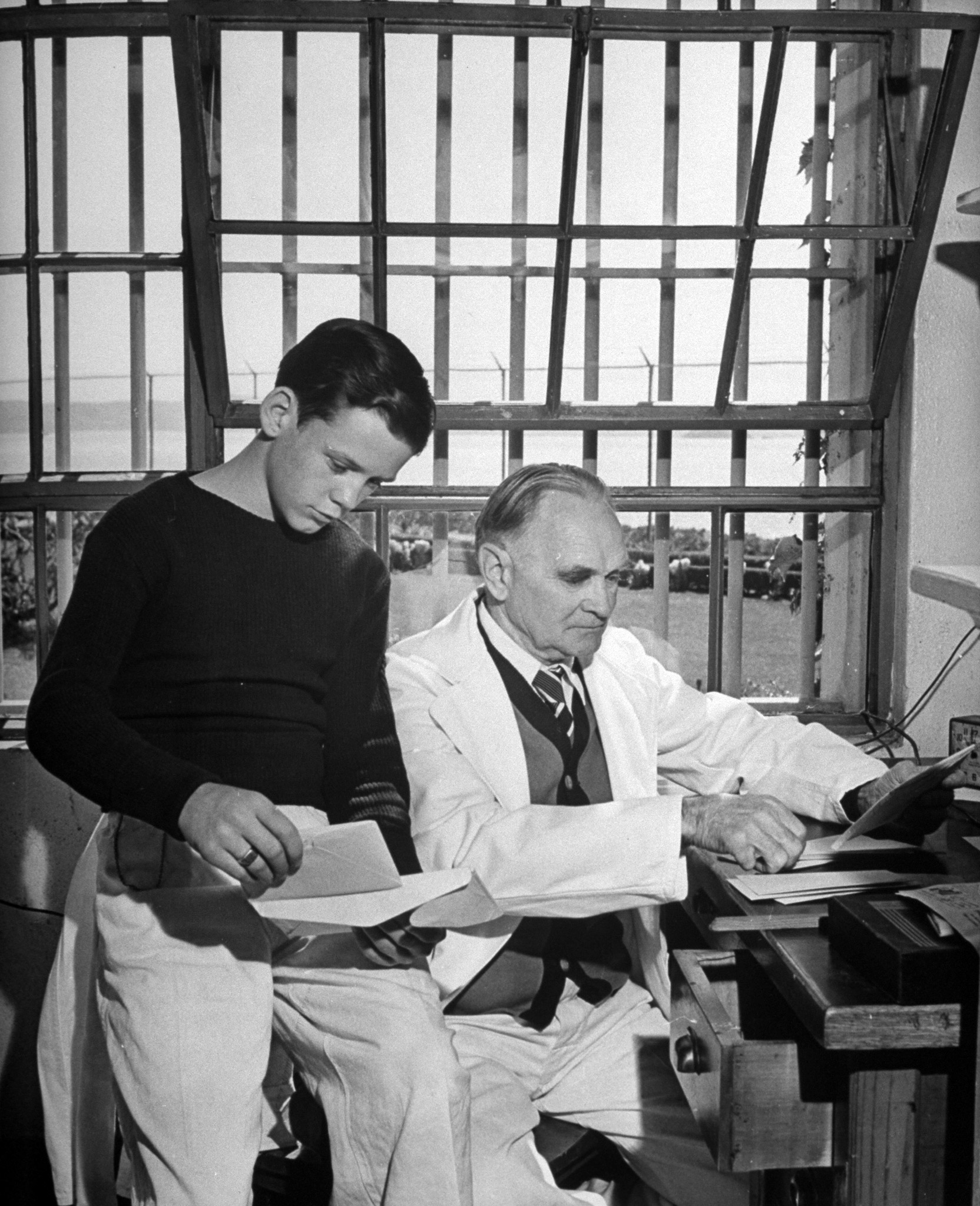

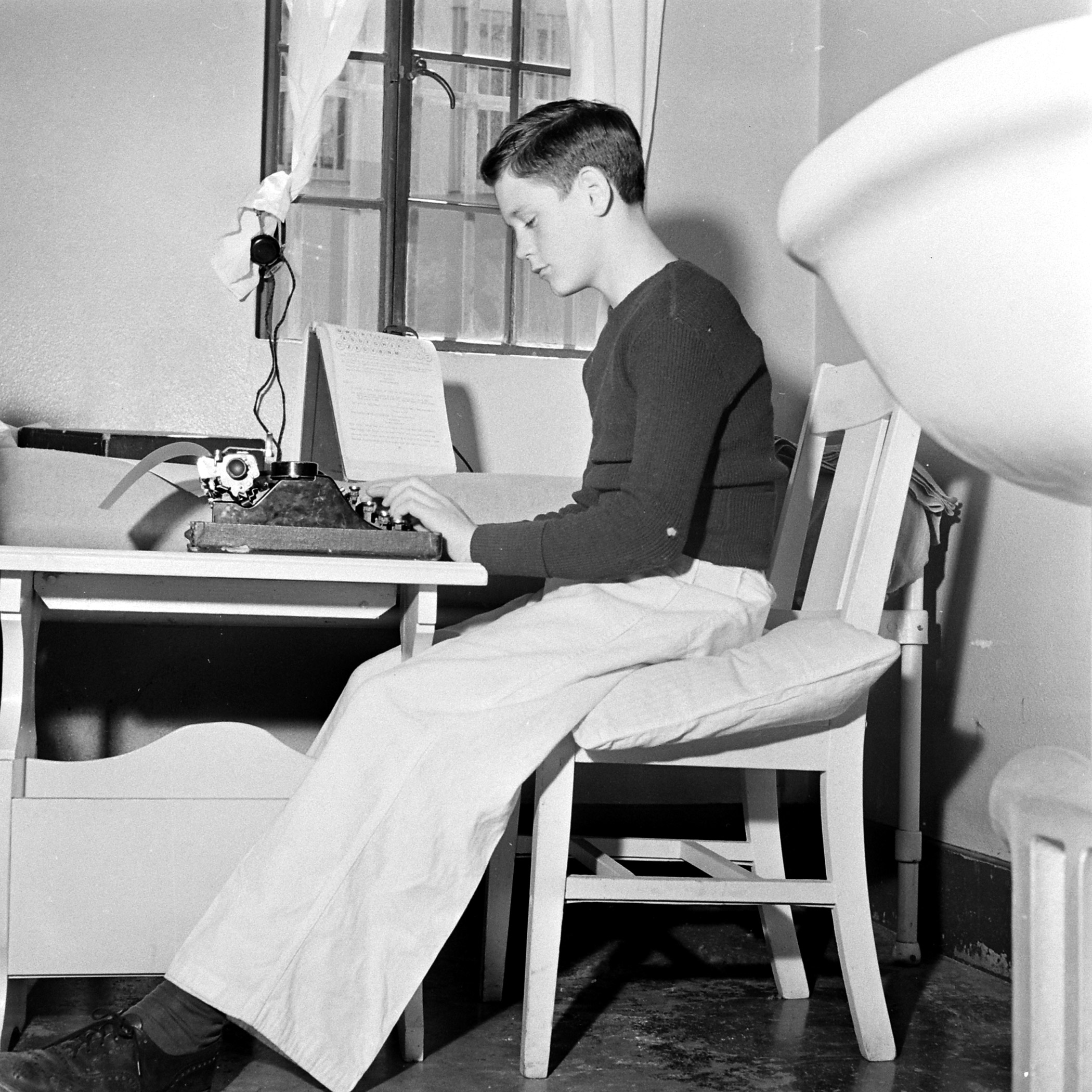

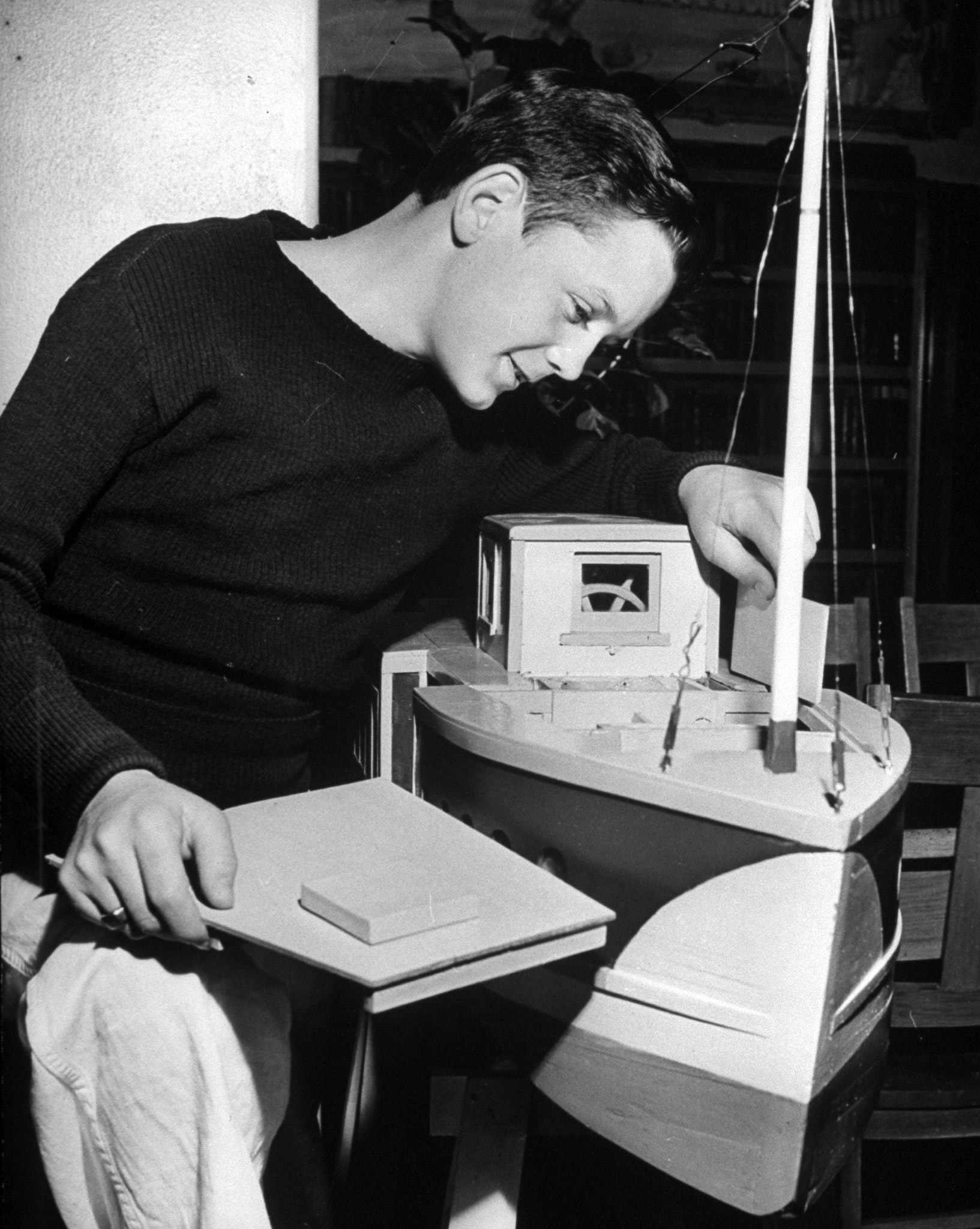

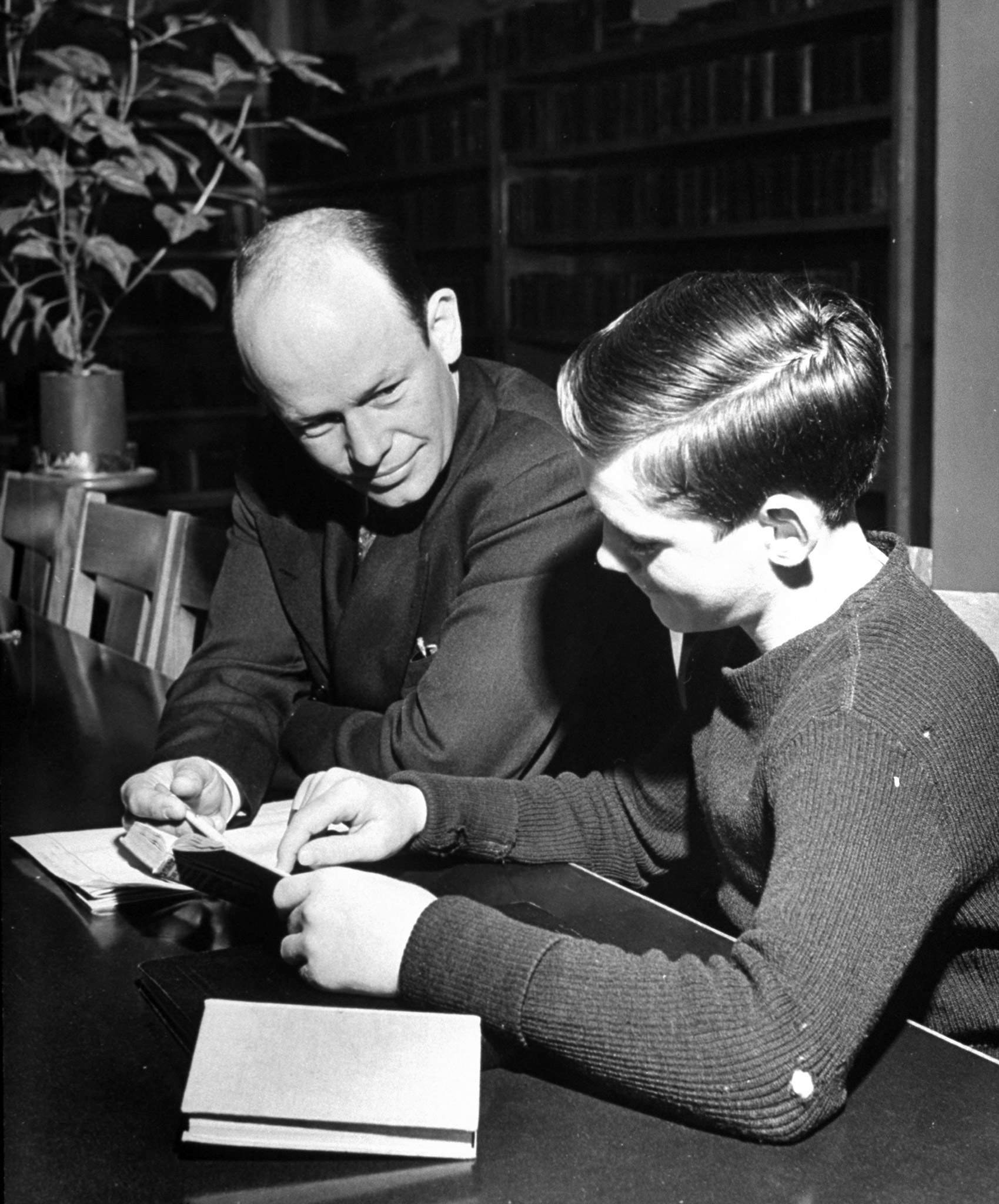

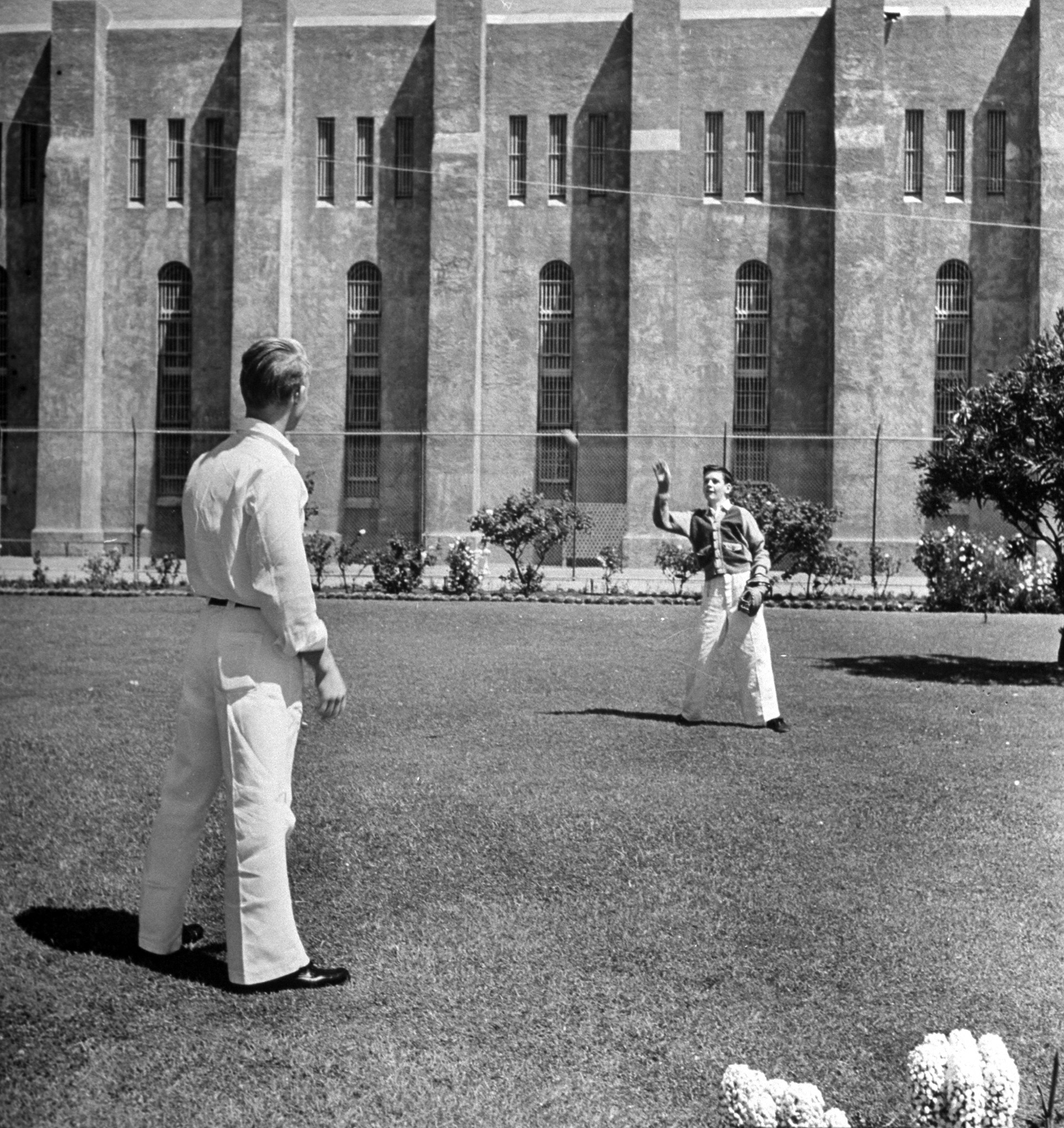

“The kid is quiet,” the photographer J.R. Eyerman jotted down in his notes as he observed 14-year-old Barney Lee on a summer afternoon in July 1941. “He is very interested in the planes overhead all day from nearby Hamilton Field,” he continued, referring to the new defense compound in Novato, Calif., 25 miles north of where they were stationed. Eyerman had been commissioned to document a day in the teen’s life, and found him—along with marveling at hovering aircraft—filling his time reading books with his tutor, playing with a model ship and throwing a ball around with friends.

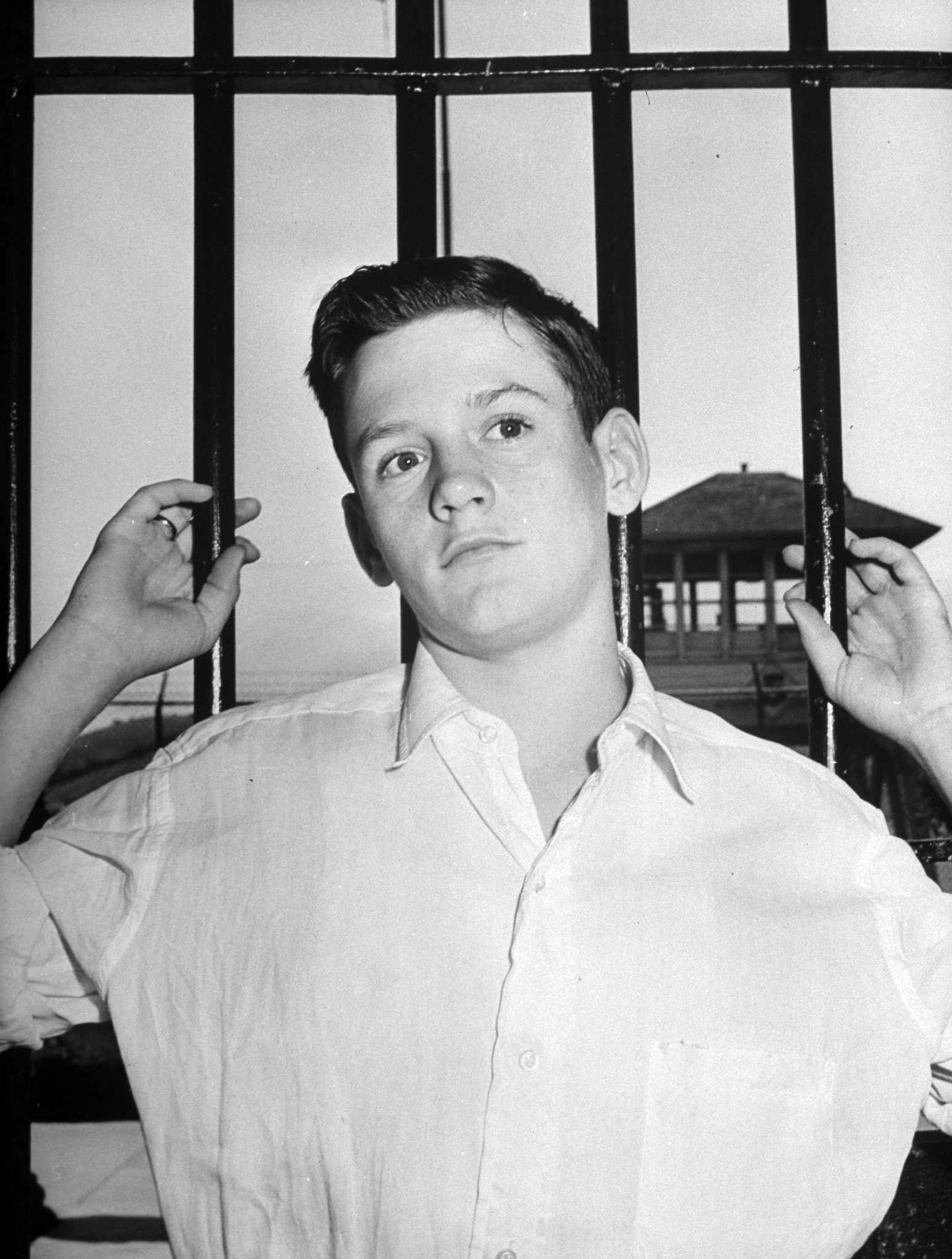

Readers who came across Eyerman’s photographs when they were published the following summer in TIME would have found various aspects of Lee’s appearance familiar, his mischievous grin and obediently tucked-in shirt reminiscent of their own sons or nephews. But Barney Lee was no ordinary adolescent. Several months prior to Eyerman’s shoot, a California court found him guilty of murdering his uncle, a farmer from Salinas in California’s Central Valley. According to responding officers, Lee fatally shot his uncle after being scolded for neglecting his farm chores. The judge who presided over Lee’s case sentenced him to five years to life in prison, earning him the title of the youngest “lifer” in California history. When Eyerman watched him playing baseball and eating dinner in a cafeteria, he did so from inside the walls of San Quentin, which Lee now called home.

Lee might have been the youngest teenager to receive a life sentence, but he was not the first. Two teenagers, one 15 years old and the other 16, had once called San Quentin their lifelong home. The fact that Lee was living alongside some of California’s most violent criminals was not unprecedented, either. In 1941, California counted itself among a handful of states that made no distinction between those convicted of murder, no matter their age. Teenagers shared cells with inmates of all ages, an arrangement that reflected a larger penal philosophy known as the “custodial model,” which emphasized discipline, direct surveillance and physical punishment. According to this model, the inmate’s identity—young or old, black or white, female or male—no longer mattered, for it was eclipsed by a crime committed against a society eager for retribution.

But things were changing. After a series of crises in the early decades of the 20th century, including highly publicized prison escapes, instances of administrative corruption and social unrest stemming from convict labor abuse, criminologists, politicians, and civic reformers came together to craft and implement a new “progressive” program. As part of the new “reformative model,” inmates were encouraged to spend more time outside their cells taking classes, exercising and bonding in group settings and receiving vocational training to increase their likelihood of post-prison employment. Rehabilitating the fallen individual, rather than punishing the unredeemable collective, became the goal of the new penal order.

When San Quentin received Barney Lee as an inmate in 1941, the administration no doubt saw him as an ideal vehicle through which to showcase the prison’s transformation under the watch of a new chief warden, Clinton Duffy. Duffy had arrived with a robust reformative agenda, which included eliminating physical punishment, introducing night school, allowing prisoners to publish a newspaper and run their own radio station and establishing an on-site Alcoholics Anonymous chapter. The photographs of a smiling, well-dressed Lee shaving in front of a bathroom mirror, enjoying the fresh air on walks and typing away at his personal desk—all under the watch of specialists—testified to the dramatic changes that were ushered in during Duffy’s tenure.

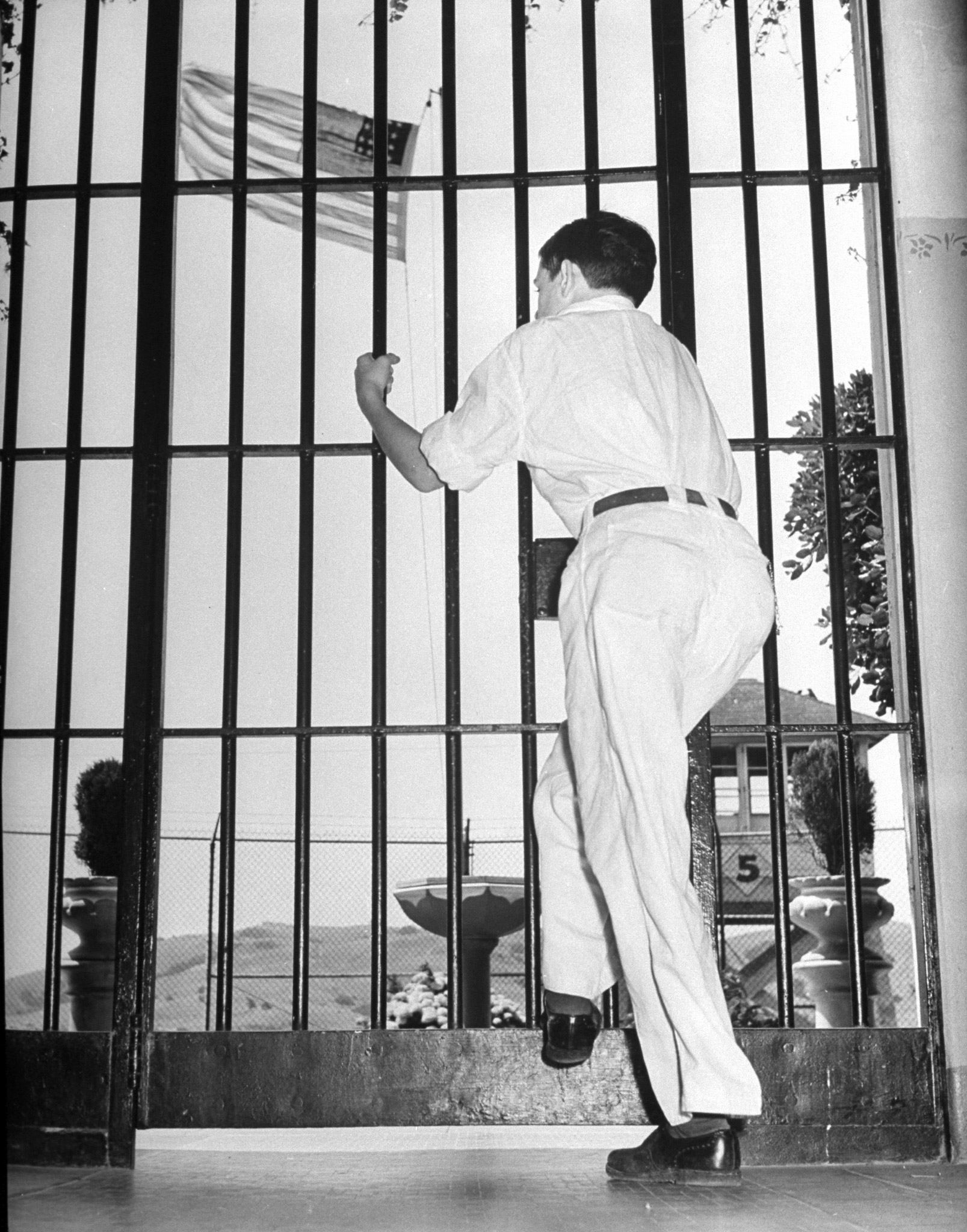

Yet Eyerman seemed to sense that he was not getting an authentic tour of the prison compound, noting in particular how the youngster’s custodians anxiously curated the photo shoot. “[The] warden refused us permission to photograph Barney with ‘hardened criminal types,’” he remarked, adding that “[The warden] is strictly against using gag photographs of any description.’” Like the inmates themselves, the photographer’s movements on the premises were restricted, reminding the photographer of the limits of even this most humane prison regime. Two portraits of Lee—one of him leaning his back against a barred gate, another of him embarking on what looks like a dispassionate escape over the same gate—can be read as the photographer’s attempt to capture the fundamental lack of freedom at the core of the American prison experience.

Eyerman was not the only one to notice San Quentin’s shortcomings. Public citizens and state officials alike had been clamoring for more lenient treatment of young offenders for some time, and Lee’s case proved to be the last straw. In 1943, the newly formed California Youth Authority assumed the role of Barney Lee’s parent as part of a new statewide initiative based on the concept of parens patriae, or “the state is the parent.” Lee was transferred to the all-boy Whittier State Reformatory, where he became the first ward in an environment that promised to apply new research on juvenile delinquency prevention and treatment.

But it was only a matter of time until Lee would outgrow his new home. In July 1943, he escaped from Whittier and spent two years working undetected as a dairyman, pantryman and bellboy throughout the American southwest, before taking his nearly $300 of savings on a gambling trip to Las Vegas. His lucky streak ended there. In September 1945, police officers became alarmed when they spotted a young boy spending an inordinate amount of money at a local store. Lee was promptly arrested under suspicion of burglary. He was 18 years old.

Liz Ronk, who edited this gallery, is the Photo Editor for LIFE.com. Follow her on Twitter @lizabethronk.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com